During research for the illustrated book, “The Heart That No One Could Burn: A Journey to Joan of Arc” (2008), the writer Jon Ewo and I travelled to France at separate times to research the story of Joan of Arc.

While Ewo gathered facts, stories, and theories about her, I collected images of how Joan of Arc is portrayed and how the events in her life are depicted.

Joan of Arc (French: Jeanne d’Arc), 1412 – 1431, is considered a heroine of France for her role during the Hundred Years’ War, and was canonized as a Roman Catholic saint. Though many people would say they know her story, there are many verbal and visual variations in a mixture of fact and fantasy.

Three of the earliest portraits of Joan: 1. Sketch by Clement de Fauquembergue, 1429, the only known depiction from her lifetime; 2. Miniature portrait from an illustrated manuscript by Martin Lefranc 1450; 3. Joan of Arc on horseback from a 1505 manuscript.

With a new digital camera, a sketchbook, and a grant from Tegnerforbundet, I travelled from Bergen, Norway to France in search of Joan of Arc. Ideas concerning how Joan of Arc’s story is pictured also became part of my then work-in-progress thesis, “Picturing Stories”.

What was I looking for? – how she was pictured, what she saw, how she was seen, and how her story was told, – so that I too could tell her story, visually.

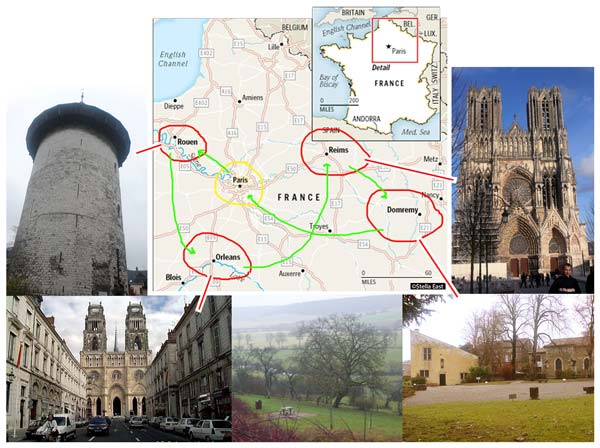

In Rouen, France I visited the marketplace where Joan had been burned, stood where she might have once stood, and saw maybe something of what she might have once seen. I saw the new cross and the new church erected in her name. I visited the tower where Joan was prisoner for a day and the little museum of her life with wax figures and all kinds of paraphernalia. From Rouen I travelled to Orleans, the city Joan rescued from the English in 1429, from Orleans to Reims where Joan witnessed Charles VII’s coronation in 1429, and from Reims to Domremy with the house where Joan was born in 1412. I spent the night there in the Domremy bed and breakfast to be as close as possible to Joan’s beginning.

Three contrasting portraits of Joan: 1. An engraving from a book by Voltaire, 18th century; 2. A statue photographed on my journey; 3. An engraving by L. Gaultier, 1612.

I photographed motifs of Joan on porcelain plates, in comic strips, as wax figures, statues, etchings, paintings, and so forth. I found these motifs in art galleries, museums, public places, and at the Mediatheque d’Orleans at The Joan of Arc Centre in Orleans. This center houses over 20,000 printed materials and over 4000 photographic documents displaying representations of Joan of Arc from the fifteenth century to the present. Over the years, depending on the political or religious circumstances, Joan of Arc has been portrayed as a woman in armour with long hair and a dress, as a woman with short hair and in man’s clothing, as Judith or as Solome from the bible, as a shepherdess, as a personification of the concept of Liberty, as the goddess of Liberty herself, as a virgin, as a saviour, and so forth. With each portrayal, Joan is given new qualities and characteristics through the concepts each identity represents. I would like to thank Olivier Bouzy at The Joan of Arc Centre for explaining to me how some of the following transformations and portrayals have been borrowed and changed within time:

Joan resembling Judith and Salome: 1. The earliest painting of Joan of Arc, 1581; 2. An illustration from “Memoirs of Joan D’Arc”, London, 1812; 3. Painting of Salome by Lucas Cranach the Elder c. 1530; 4. Painting of Judith by Lucas Cranach the Elder c. 1530.

Joan resembling “Liberty”: 1. Painting by Eugene Delacroix, (“La liberte“) “Liberty Leading the People 1833”; 2. Engraving of Joan by J.C. Buttre, via Corbis, 19th-century; 3. Joan at the “Siege d’Orleans en 1429”, engraving by Antoine Borel, 18th century; 4. Painting of Joan at Orleans.

Each event in Joan’s life, such as witnessing the crowning of the king, and when she was burned, etc. has been pictured in thousands of different ways. These pictures not only vary through the portrayal of different given identities, but also how the scene is compositionally staged, how qualities such as sorrow, pride, brutality, victory, compassion, and captivity, are depicted, and from which point of view we as viewers are given. Even though this story has been told visually for over 500 years, and even though conventions and ways to picture stories have changed, Joan’s story is still recognizable.

Verbal language, claims the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, is a system of signs that has only a potential life dependent on a community of speakers, which in turn are dependent on the presence of time for the allowance of both change and continuity. The changes and continuity of the visual tellings of Joan, prove how the language of pictures, are also influenced by time and change among a community of picture users.

Just as the verbal story could be told with another set of illustrations instead of mine, so could my illustrations tell the Joan of Arc story with a different manuscript. It is her story I illustrate and not the actual words. My visual story is based on what I learned through this research and the choices I made as a storyteller: such as how to depict her flag, her armour, her facial features, the colour of her horse, and how she carried her sword. The enormous diversity among the numerous ways that Joan’s story has been visually told, demonstrates the power, authorship, and integrity of visual storytelling.

©Stella East

This is a very nice presentation.

Thank You

Thank you Heather 🙂

I love Joan D’Arc

I have framed a copy of painting of her

With Priests and Monks bowing to her

next to her. I should know the Artist’s

Name! Is it Titian?

I want to read more to find out what

Was going on politically-religiously at her

Time, Very complicated

I feel her spirit very close to me

Thank You for this wonderful article.

Thank you Lisa, So nice that you liked my article. It makes me especially happy since you are so connected to her.

Stella